Case Studies

The Brontë Sisters

The three Brontë sisters — Charlotte, Emily and Anne- grew up with their brother Branwell in Parsonage House in Haworth, Yorkshire. Their childhood was blighted by the deaths of their mother from cancer, and their elder sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, from tuberculosis.

Their father Reverend Patrick Brontë was understandably a somewhat melancholy character, and the children depended on writing stories to entertain themselves. Creating sophisticated sagas about imaginary countries and kingdoms, they developed literary skills which they took with them into adulthood.

Parsonage House famously stands within an area of expansive moorland, which they were allowed to roam on as children, and which would have given their imaginations free rein. The harsh landscape formed the inspiration for the windswept, treacherous moors immortalised in Emily’s most famous work, Wuthering Heights

All three worked occasionally as governesses, and in 1841 we can see that Charlotte is working away in this capacity whilst Emily and Anne remain at home. They all disliked the job, and Charlotte and Anne both wrote novels (Jane Eyre and Agnes Grey) which describe its perils, and the general pressures on women of their social standing during this period. They could marry, find work as a governess or servant, or remain with their families- but couldn’t easily achieve a meaningful independence.

Parsonage House - The home of the Brontës

Their writing allowed them to explore and document this situation. Ironically, due to the restrictions of the time, their poetry and novels were published under the male pseudonyms of Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell- three brothers rather than sisters.

Their works are very different, but share common strengths of innovation and vision, particularly Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights, which both received a decidedly lukewarm reception on their initial publication, but are now hailed as classics.

Jane Eyre makes a heroine of a self-confessedly imperfect, plain and spirited woman, who stands up to the male hero of the novel- her employer, and social superior- and wins his affections with a studied lack of deference.

Wuthering Heights is unashamedly passionate and ambitious, and allowed Emily Brontë to explore her gift for lyrical, intensely poetic writing.

Emily Brontë

All three are to be found on the 1841 census, but Emily died of tuberculosis in 1848 and Anne of an unknown illness a year later, and only Charlotte appears, back in Haworth, on the 1851. She died in 1855, having revealed her true identity as the author of Jane Eyre only a few years previously.

With that information in hand, I set out to look for their census records in the Yorkshire 1841 & 1851 Census CD sets from British Data Archive.

I looked up Charlotte Brontë on TheGenealogist.co.uk by doing a search under the 1841 Yorkshire census transcripts, and immediately found her. I decided to view an image of the census record (see the excerpt below) and found her to be living at Upper Road House. The search results informed me that I could also find this record on the CD set (CD 28, HO107 / 1313 / 7, folio 13).

After my success with Charlotte, I decided to tackle the other two sisters, Emily and Anne. I searched for Emily first, again on TheGenealogist.co.uk, loaded up the census image, and found her living at Parsonage House with her sister Anne and their father Patrick. The search results showed me that I could also find this record on the CD set (CD21, HO107/1295/6/, Folio 41).

Charlotte Brontë :

Emily, Anne and Patrick Brontë :

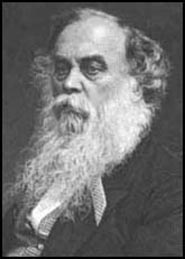

Sir Titus Salt

Sir Titus Salt, businessman and philanthropist, was though a model employer in every sense. Born in 1803 in Yorkshire, he was the son of Daniel Salt, a woolstapler, and in 1833 took over the family business to great success, becoming the largest employer in Bradford- making fine cloths from donskoi and alpaca wool. Bradford was badly polluted- over 200 factory chimneys made the air unhealthily smoky, and sewage was regularly dumped in the river, also a source of drinking water. Cholera and typhoid were common, and the appalling life expectancy of 18-20 was one of the lowest in the country.

During the 19th century, advancements in technology meant that industrial activity expanded at an unprecedented rate. Thousands of people came from the countryside to cities and towns to work in mills and factories that were hastily set up to take advantage of new manufacturing methods. Employment boomed, but in a rush for production at the cheapest possible rates, workers’ rights often took a back seat.

Titus was one of very few to show concern. He even created the Rodda Smoke Burner, which meant that factory smoke contained far fewer pollutants. He introduced them into his factories, and when he became the mayor in 1848, tried hard to pass a by-law enforcing their general use, to try and make a real difference.

The other factory owners stood firm against it though, and Titus, showing an imagination beyond that of his peers, decided to construct an entirely new industrial community called Saltaire, in a rural location on the banks of the River Aire.

The textile mill he built was the most modern in Europe, and was designed to provide a safer, healthier working environment for staff. Noise was reduced by placing some machinery underground. Dust and dirt were removed from the factory by flues. Salt’s smoke burners were fitted throughout, so that the air outside wasn’t polluted.

850 houses were built for workers- amongst a park, a church, a school, a hospital, a library, almshouses and shops. Salt’s choices showed great humanism- every house had fresh water, gas lighting and heating, an outside lavatory. The streets were named for his wife and children and for the architects.

Salt was also a political man, a one-time MP. In 1869 he was made a baronet by Queen Victoria. In 1876 the last building in Saltaire was completed, and later that year Sir Titus Salt died at his home. A much-loved figure, 100,000 people attended his funeral. He is buried at Saltaire Congregational Church.

Saltaire mills from the Leeds and Liverpool Canal

Sir Titus Salt can be found in the 1841, 1851, 1861, and 1871 censuses dying in 1876, aged 73.

I looked Titus up on TheGenealogist.co.uk by doing a search under the 1841 Yorkshire census transcripts, and immediately found him. I decided to view an image of the census record (see the excerpt below) and found him to be living at Horber Road, Bradford. The search results informed me that I could also find this record on the CD set ( CD20 H1071294.pdf, p.22).

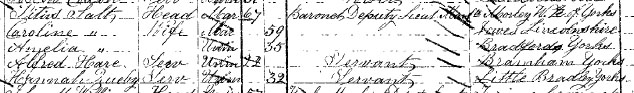

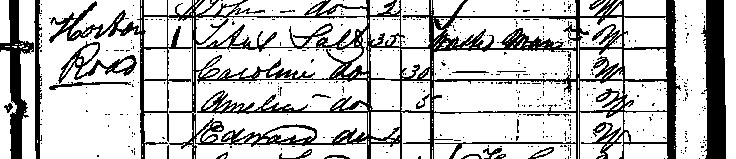

After my success in 1841, I decided to tackle the other years, 1851, 1861 and 1871. Again I searched on TheGenealogist.co.uk, loaded up the census images, one by one and found him living at Crows Nest, Halifax in 1851 ( CD9 H72297_2.pdf, p.147). Methley Hall, Pontefract in 1861 ( CD13 RG9_3432.pdf, p.127) and, knowing he had been living in London at the time of the 1871 census, I found him in Westminster, living with his wife, Caroline, and his daughter, Amelia in 1871 ( CD7 RG10-133.pdf, p.43).

1841 :

1871 :